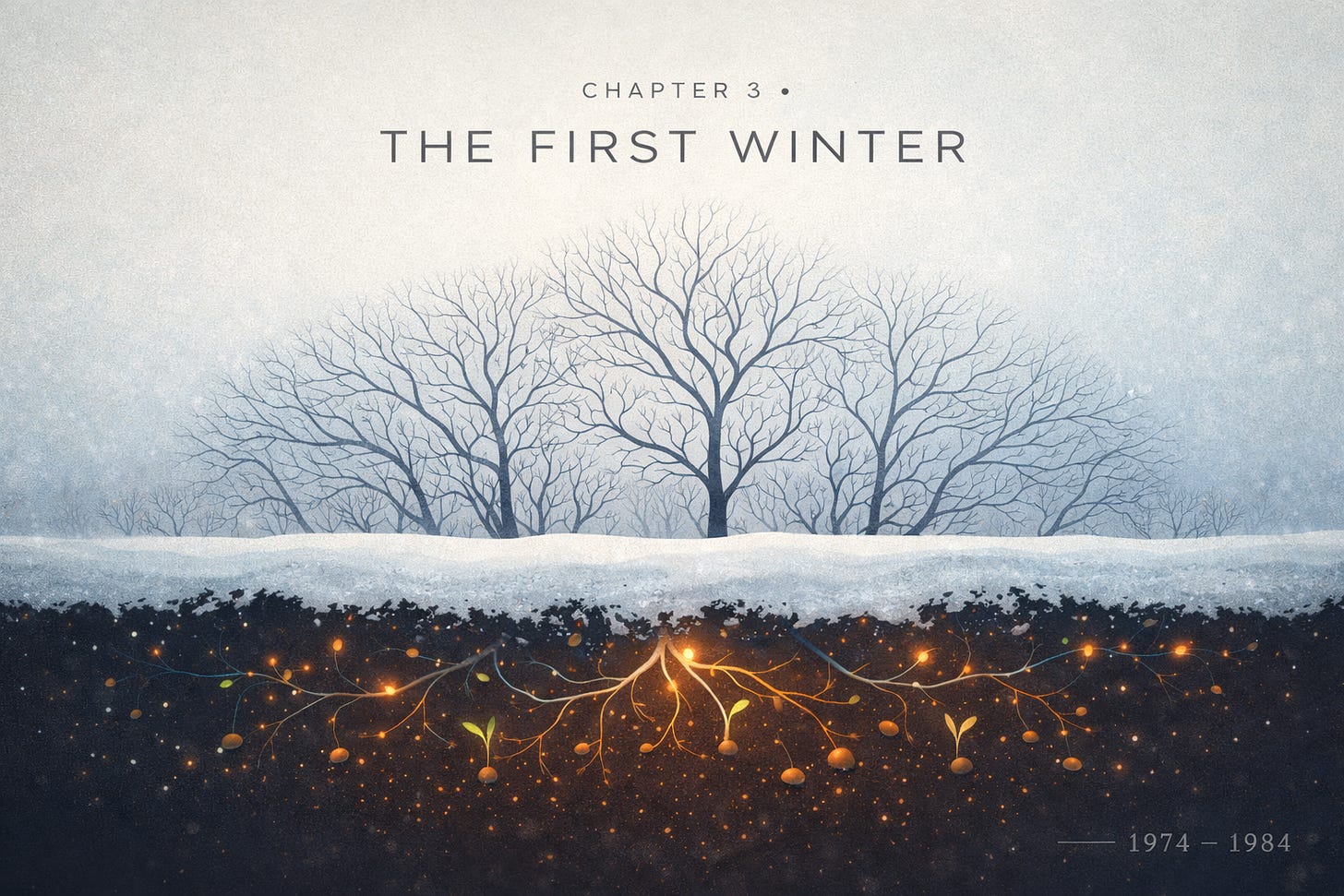

The First AI Winter

What happened when the money ran out and the promises failed. What failure taught that success never could.

This is Chapter 3 of A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence.

In 1973, the British government commissioned a mathematician named James Lighthill to evaluate the state of artificial intelligence research. Lighthill was a distinguished scientist—later knighted, later Master of Trinity College, Cambridge—with impeccable credentials and no particular axe to grind. His report was measured, fair-minded, and devastating.

AI research, Lighthill concluded, had failed to deliver on its promises. The successes were confined to narrow “toy problems” that bore little resemblance to real-world challenges. The techniques didn’t scale. The grand vision of general-purpose intelligence remained as distant as ever. And perhaps most damning: there was no reason to believe continued funding would change this.

The report recommended that most AI research funding in the UK be terminated.

The government accepted the recommendation. British AI research collapsed almost overnight. Labs shut down. Researchers scattered to other fields or emigrated. An entire generation of potential AI scientists never materialized because there were no positions, no funding, no future in the field.

In the United States, DARPA—the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency that had funded much of American AI research—reached similar conclusions. The money didn’t disappear as suddenly as in Britain, but the message was clear: the promises of the 1950s and 60s had not been kept. Funding declined sharply. Universities closed AI labs. Companies abandoned AI projects.

The first AI winter had begun. It would last a decade.

What made the collapse so brutal wasn’t just the funding cuts. It was the realization that the optimism had been misplaced. The problem wasn’t one of engineering—building better hardware, writing more efficient code, encoding more rules. The problem was fundamental. The approach itself was wrong.

You could not, it turned out, program your way to general intelligence.

The Toy Problem Critique

The Lighthill Report crystallized criticisms that had been building for years. The central charge was simple: AI researchers were solving toy problems and claiming to have solved intelligence.

What’s a toy problem? A problem that’s been simplified, constrained, and sanitized until it’s barely recognizable as the real-world challenge it’s supposed to represent.

Take the “blocks world” that many AI systems operated in during the 1960s and 70s. A simulated world containing only perfect geometric blocks—cubes, pyramids, rectangular prisms—on a flat surface. The system could answer questions like “What color is the block on top of the red pyramid?” or follow commands like “Put the blue cube on the green block.”

This was presented as progress toward natural language understanding and spatial reasoning. And within its domain, it worked. The systems could parse sentences, maintain internal representations of the world state, plan sequences of actions, and execute them.

But the blocks world bore almost no resemblance to reality. Perfect shapes. Perfect lighting. Perfect information about the world state. No ambiguity. No uncertainty. No irrelevant objects. No complexity beyond what was explicitly programmed.

Real vision systems had to deal with shadows, occlusion, varying lighting, dirt, wear, similarity, ambiguity. Real language understanding had to handle idioms, context, implication, sarcasm, reference. Real spatial reasoning had to work with imperfect information, three-dimensional complexity, physics.

The blocks world was a toy. And AI researchers had built exquisite toys that worked perfectly in their toy worlds and failed immediately when confronted with reality.

Critics pointed to similar toy problems everywhere. Chess was a toy problem—perfect information, formal rules, no ambiguity. Theorem proving was a toy problem—formal axioms, mechanical inference, no real-world grounding. Even medical diagnosis in expert systems was a toy problem—a narrow domain with well-defined rules, expert knowledge that could be articulated, and clear decision criteria.

The techniques that worked in toy domains didn’t scale to real ones. The gap between toy and reality wasn’t a matter of degree. It was a difference in kind.

The Frame Problem Revisited

One particular problem came to symbolize the fundamental limitation: the frame problem, which we touched on in the last chapter but which now became impossible to ignore.

The frame problem asked: how does a system know what’s relevant? When you act in the world, how do you know which facts might change and which will stay the same?

Pick up a cup of coffee. What changes? The cup’s location. Your hand’s position. The center of gravity of the cup-hand system. The visual appearance from different angles.

What doesn’t change? The color of the cup. The liquid inside. The temperature (well, slowly). The existence of the table. The laws of physics. The contents of the room. The weather outside. Yesterday’s election results. The mass of Jupiter.

Humans just know what’s relevant. We have an intuitive sense of which facts matter for which actions. We don’t consciously run through a checklist of everything in the universe that might or might not change when we pick up a cup.

But programs had to be told. Everything had to be specified. And you couldn’t specify everything without an infinite regress.

Researchers tried various approaches. Some attempted to explicitly mark which facts were “frame axioms”—things that don’t change unless explicitly changed. But this required enormous numbers of axioms for even simple domains. Others tried non-monotonic logics or default reasoning. But these introduced new complexities and solved the problem only in restricted cases.

The deeper issue was that relevance isn’t a logical property. It’s contextual, pragmatic, learned from experience. Humans know what’s relevant because we’ve seen thousands of similar situations. We’ve built up intuitions about cause and effect, about what typically changes and what typically doesn’t.

This was knowledge that resisted formalization. You couldn’t write it down as rules because it wasn’t rules. It was patterns extracted from experience. And symbolic AI had no way to extract patterns from experience. It could only follow rules that humans explicitly programmed.

The Commonsense Problem

Then there was the “commonsense knowledge” problem, which turned out to be even harder than the frame problem.

Consider the sentence: “John decided not to have soup for lunch because he’d forgotten his spoon.”

You understand this immediately. But look at what you had to know to understand it:

Soup is typically eaten with a spoon

Lunch is a meal

People usually eat during meals

If you don’t have the right utensil, eating is difficult

“Forgetting” means not having something with you

This is a sufficient reason to choose different food

None of this is stated. All of it is implicit. And it’s just the tip of the iceberg. Understanding even simple sentences requires vast amounts of background knowledge about how the world works, how people behave, what’s typical and what’s not.

Researchers tried to encode commonsense knowledge explicitly. The CYC project, started in 1984 by Doug Lenat, attempted to build a comprehensive ontology of commonsense knowledge. The goal was to encode millions of facts and rules that “everyone knows”—things like “you can’t be in two places at once” and “when you let go of something, it falls” and “dead people don’t make purchases.”

Decades later, CYC contains millions of assertions. It remains incomplete. The scope of commonsense knowledge is staggering—every culture, every domain, every context has its own implicit knowledge. And the knowledge isn’t static; it evolves, shifts, adapts to new situations.

More fundamentally, much commonsense knowledge isn’t propositional—it’s not facts you can state. It’s intuitions, patterns, heuristics learned from experience. A chef knows when bread dough “feels right” not from following rules but from making thousands of loaves. A driver knows when to slow down on a rainy curve not from calculating friction coefficients but from accumulated experience.

This kind of knowledge—experiential, implicit, pattern-based—was exactly what symbolic AI couldn’t capture. And it was exactly what general intelligence required.

A Different Path

The winter forced a reckoning. Not just about funding or timelines, but about the fundamental approach.

Some researchers doubled down. They argued that symbolic AI just needed more time, more computational power, more rules, better knowledge representation schemes. The approach was right; it just hadn’t been given enough resources to succeed.

Others began to question the premises. Maybe intelligence wasn’t symbol manipulation. Maybe reasoning wasn’t logical inference. Maybe knowledge wasn’t rules and facts encoded in formal structures.

A few researchers—a minority, largely ignored during the winter—kept working on something different: neural networks. Systems inspired (loosely) by biological brains. Systems that learned from examples rather than following programmed rules. Systems that extracted patterns from data rather than having patterns explicitly encoded.

These ideas weren’t new. Frank Rosenblatt had built the Perceptron in the late 1950s—a simple learning system that adjusted its internal parameters based on examples. It had shown promise. But in 1969, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert published “Perceptrons,” a mathematical analysis that showed fundamental limitations of simple neural networks.

The book was technically correct about what single-layer perceptrons couldn’t do. But it was widely interpreted as proof that neural networks in general were a dead end. Funding dried up. Research moved to symbolic approaches. Neural networks became unfashionable, almost taboo.

During the winter, a handful of researchers—Geoffrey Hinton, James McClelland, David Rumelhart, Yann LeCun, others—kept working on neural networks. They developed new architectures, new learning algorithms. They showed that multi-layer networks could learn complex functions that single-layer networks couldn’t. They demonstrated applications in speech recognition, image processing, control systems.

They were largely ignored. The field had committed to symbolic AI. Neural networks were yesterday’s failed idea.

But they were patient. And they were right.

Five Lessons from Failure

The AI winter taught several crucial lessons, though it would take years for the field to fully absorb them.

Lesson 1: Scaling formal systems doesn’t work.

You can’t solve the knowledge problem by encoding more knowledge. You can’t solve the brittleness problem by adding more rules. You can’t solve the frame problem or the commonsense problem by being more systematic about specification. These aren’t engineering challenges—they’re fundamental limitations of the approach.

Lesson 2: Real-world complexity defeats symbolic approaches.

Toy problems are solvable with formal methods. Real problems aren’t. The gap between toy and reality isn’t one you can bridge by incremental improvement. It requires a different approach entirely.

Lesson 3: Intelligence requires learning.

Humans don’t come pre-programmed with rules for every situation. We learn from experience. We extract patterns from examples. We generalize from specific cases. We adapt to new situations by recognizing similarities to old ones.

Any system that can’t learn from experience isn’t going to achieve general intelligence, no matter how sophisticated its programming.

Lesson 4: Most knowledge is implicit.

The knowledge required for intelligence isn’t all articulable. Much of it is intuitive, heuristic, contextual. It’s not rules and facts but patterns and dispositions. You can’t encode it by asking experts to state what they know. You have to extract it from observation of what they do.

Lesson 5: Moravec’s Paradox reveals our ignorance.

The fact that hard things are easy and easy things are hard for computers tells us that we don’t understand intelligence as well as we thought. Our intuitions about what’s “simple” and what’s “complex” are backwards because we’re not aware of the massive computation underlying our effortless abilities.

These lessons pointed toward a different approach: not programming intelligence but growing it. Not encoding knowledge but learning it from data. Not specifying behavior but training systems to exhibit appropriate behavior through experience.

But in 1980, nobody quite knew how to do that at scale. The pieces existed—learning algorithms, neural networks, statistical pattern recognition—but they hadn’t been put together into something that could match or exceed symbolic AI’s capabilities.

The winter would eventually thaw. But not because symbolic AI figured out its problems. Because a different approach—one that had been dismissed and discarded—would prove successful.

The Knowledge That Comes from Failure

There’s a particular kind of knowledge that only comes from failure.

Success teaches you that your approach works. It validates your assumptions. It encourages you to continue along the same path, to refine and extend what you’re doing.

Failure—real, fundamental failure—forces you to question your assumptions. It makes you ask whether you’re solving the wrong problem, using the wrong tools, following the wrong path entirely.

The AI winter was a failure of that kind. Not a temporary setback or an engineering challenge, but a fundamental failure that revealed the limitations of an entire approach.

For researchers who lived through it, the winter was brutal. Careers ended. Dreams died. A decade of work seemed wasted. The field that had promised to revolutionize everything delivered expert systems that couldn’t learn and game-playing programs that couldn’t generalize.

But failure taught what success never could: intelligence is not programmable in the way they’d imagined. It’s not rules and symbols and logical inference, or at least not primarily. It’s something that emerges from learning, from experience, from extracting patterns from vast amounts of data.

You can’t build intelligence by telling machines what to think. You have to teach them how to learn.

The winter proved this. Not through argument or theory, but through the hard evidence of ambitious projects that failed, promising approaches that didn’t scale, and brilliant engineers who couldn’t make symbolic AI work no matter how hard they tried.

By the mid-1980s, the lesson was becoming inescapable. The path forward lay not in programming intelligence, but in something researchers had mostly abandoned a decade earlier: neural networks that could learn.

But it would take another breakthrough—and another decade—before that path would prove successful.

In Retrospect

In retrospect, the AI winter of 1974-1984 (some count it extending into the early 1990s) was necessary. Not just financially necessary to clear out failed approaches and redirect resources, but epistemologically necessary—necessary to learn what couldn’t be learned from success.

The field had to discover that intelligence wasn’t what they thought it was. That the elegant mathematical logic of symbol systems was too brittle, too narrow, too disconnected from how intelligence actually works.

They had to learn that the hard problems weren’t the ones that looked hard to humans (logic, math, formal reasoning) but the ones that looked effortless (vision, language, movement, common sense). That these “easy” problems required different techniques—not explicit programming but implicit learning.

Most fundamentally, they had to learn humility. The confidence of 1956—”we’ll solve this in eight weeks”—had been replaced by something more realistic. Intelligence was harder than they’d thought. General intelligence might take not decades but generations. And it might require approaches they hadn’t yet imagined.

The winter killed symbolic AI’s dominance. It didn’t kill symbolic AI itself—logic and rules and knowledge representation remained useful for specific applications. But it ended the dream that you could encode your way to general intelligence.

What emerged from the winter, slowly and against great resistance, was a different dream: that you could grow intelligence by training systems on vast amounts of data. That learning, not programming, was the key.

The pieces were all there, waiting to be assembled. Neural networks that could learn complex functions. Backpropagation algorithms that could train deep networks. Increasing computational power. And crucially, the hard-won knowledge that the old approach didn’t work.

Sometimes you have to learn what doesn’t work before you can discover what does.

The path forward lay not in programming intelligence, but in something no one quite knew how to do yet: teaching machines to learn.

But they would figure it out.

Notes & Further Reading

The Lighthill Report (1973):

Lighthill, J. (1973). “Artificial Intelligence: A General Survey.” Published as a report for the UK Science Research Council. Also known as the Lighthill Report, it’s devastatingly fair—crediting genuine achievements while concluding that AI had not delivered on its promises and was unlikely to do so with continued funding. Available through various AI history archives.

The AI Winter:

The term “AI winter” was coined by analogy to nuclear winter. The first winter is generally dated 1974-1980 (some extend it to the early 1990s). For firsthand accounts, see Crevier, D. (1993). AI: The Tumultuous History of the Search for Artificial Intelligence. McCorduck, P. (2004). Machines Who Think (updated edition) also covers this period.

The Frame Problem:

McCarthy, J., & Hayes, P.J. (1969). “Some Philosophical Problems from the Standpoint of Artificial Intelligence.” Dennett’s philosophical essays on the frame problem remain the most accessible introduction: Dennett, D. (1984). “Cognitive Wheels: The Frame Problem of AI.”

Commonsense Knowledge and CYC:

Lenat, D.B., & Guha, R.V. (1989). Building Large Knowledge-Based Systems. The CYC project began in 1984 and continues today, though it has not achieved its original ambitious goals. It represents both the promise and the limitations of encoding commonsense knowledge explicitly.

Blocks World:

Winograd, T. (1972). “Understanding Natural Language.” SHRDLU, Winograd’s blocks world system, was celebrated as a breakthrough in natural language understanding. But as critics noted, it worked only in an absurdly simplified domain and didn’t scale to real language understanding.

Perceptrons and Neural Network Suppression:

Minsky, M., & Papert, S. (1969). Perceptrons: An Introduction to Computational Geometry. Technically rigorous about the limitations of single-layer perceptrons, but widely misinterpreted as proving neural networks in general couldn’t work. This misinterpretation set the field back by a decade.

What the Winter Taught:

The lessons of the AI winter were not immediately obvious. Many symbolic AI researchers continued to believe the approach was sound but underfunded. The full implications—that learning was necessary for general intelligence—only became clear in retrospect, after the neural network renaissance of the 1980s-90s and especially after the deep learning breakthroughs of the 2010s.

Looking Forward:

The researchers who kept working on neural networks during the winter—Hinton, LeCun, Bengio, Rumelhart, McClelland, and others—would later be recognized with Turing Awards and other honors. Their persistence through the unfashionable period laid the groundwork for modern AI. Chapter 4 tells their story.