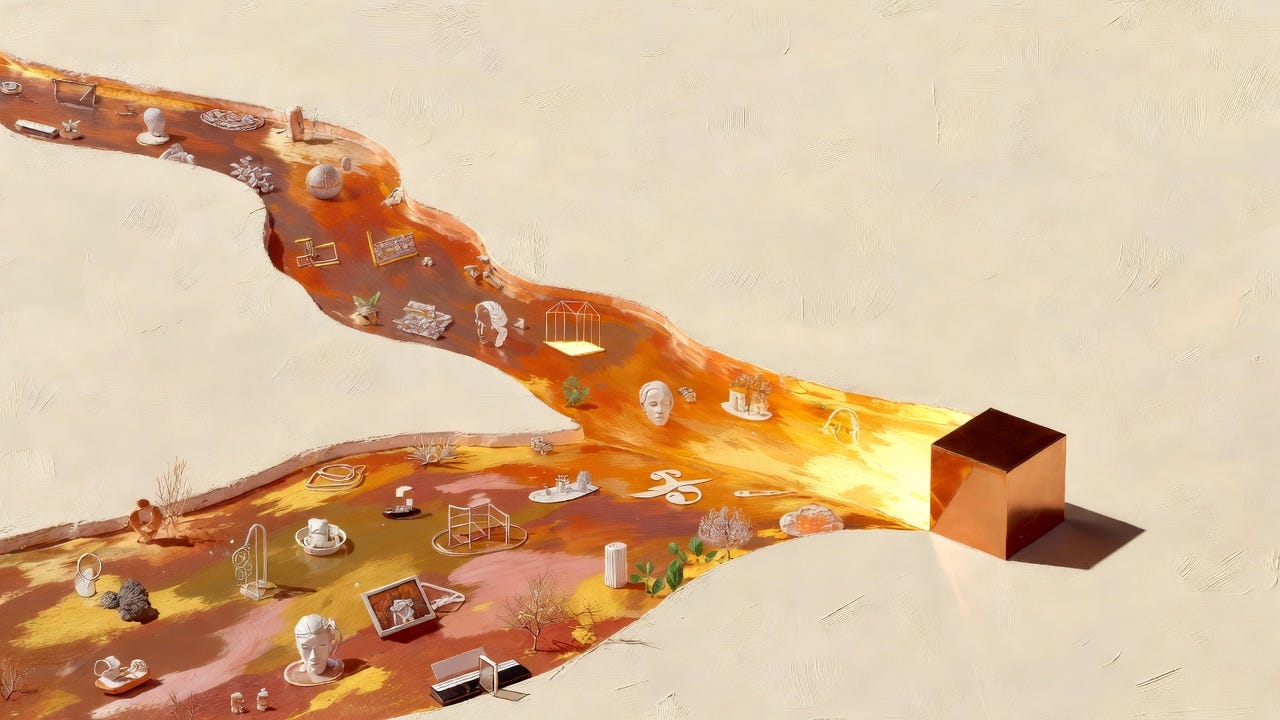

The World as Training Data

How reality itself became the teacher. Why “more data” often beats “better algorithms,” and what the scaling hypothesis revealed.

This is Chapter 5 of A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence.

In 2007, Fei-Fei Li stood before her colleagues at Princeton and proposed something audacious. She wanted to build a dataset of not thousands of images, but millions. Not ten categories of objects, but twenty thousand. Not a careful sample, but a sprawling attempt to capture the visual world.

The reaction was skeptical. “It will take forever,” someone said. “It might not even help,” said another. The conventional wisdom was clear: computer vision’s problem wasn’t data—it was algorithms. Better features, smarter architectures, more sophisticated approaches. That’s where progress would come from.

Li was a young professor, barely settled into her first faculty position. Pushing against conventional wisdom was risky. But she had watched computer vision systems fail for years, and she thought she understood why. These systems were being asked to recognize the visual world after seeing a few thousand carefully curated examples. It was like teaching someone to read using only children’s books, then being surprised when they struggled with newspapers.

“We’re data-starving our systems,” she told her research group. “They can’t learn to see the world if we only show them tiny glimpses.”

Her team built ImageNet. It took three years, millions of dollars, and an army of crowdsourced workers. Her colleagues’ skepticism seemed justified—right up until 2012, when the dataset proved that everything about computer vision needed to change.

The Small Dataset Era

In 2005, when Li was a graduate student at Caltech, the largest computer vision dataset was Caltech 101. It contained 9,000 images across 101 categories. Creating it had taken months of careful work—finding suitable images, defining clear categories, labeling each image by hand.

9,000 images sounds like a lot. But consider what it means. For 101 categories, that’s an average of 89 images per category. For “dog,” maybe 100 images. These 100 images were supposed to teach a system everything about dogness—all breeds, all poses, all contexts, all lighting conditions.

It couldn’t. The systems trained on Caltech 101 learned to recognize the specific dogs in the dataset but struggled with new dogs that looked different. They were overfitting—memorizing examples rather than extracting concepts.

Pedro Domingos, a machine learning researcher at the University of Washington, crystallized the problem in a 2012 paper: “It’s not who has the best algorithm that wins. It’s who has the most data.”

But in the mid-2000s, this wasn’t yet obvious. The dominant view was that data helped but wasn’t fundamental. Andrew Ng, then at Stanford, spent years building self-driving car systems using sophisticated algorithms on limited data. Geoffrey Hinton kept improving neural networks with better training procedures. Yann LeCun refined convolutional architectures.

Progress came slowly. Computer vision systems could recognize digits, identify faces in controlled settings, classify objects they’d seen many times before. But they couldn’t generalize. They couldn’t handle variation. They couldn’t see the way humans do.

Li thought she knew why. “We’re testing algorithms on toy problems,” she said in a 2009 talk. “We need to show them the actual world.”

A Three-Year Gamble

ImageNet started with a simple but massive ambition: photograph the visual world.

Li’s team began with WordNet, a linguistic database that organized concepts hierarchically. WordNet contained over 80,000 noun concepts—”dog” splitting into “golden retriever,” “German shepherd,” “poodle.” “Vehicle” splitting into “car,” “truck,” “motorcycle,” each splitting further into specific makes and models.

The plan: create a visual database following WordNet’s structure. For each of tens of thousands of concepts, collect hundreds of photographs showing that concept in diverse contexts.

The math was daunting. 20,000 categories times 500 images per category equals 10 million images. Each image needed verification—looking at a photo and confirming it actually showed the claimed object. At one minute per image, that’s 10 million minutes. About nineteen years of full-time work.

“Everyone told me it was impossible,” Li recalled in a 2015 interview. “My first grant proposal was rejected. Reviewers said the project was too ambitious, probably wouldn’t succeed, and even if it did, probably wouldn’t matter.”

She applied for funding from multiple sources. Most rejections cited the same concern: collecting more data wouldn’t solve computer vision’s fundamental problems. Those were algorithmic problems requiring algorithmic solutions.

Li finally secured funding from the National Science Foundation. But the money wasn’t enough to hire researchers to label millions of images. So she turned to Amazon Mechanical Turk—a crowdsourcing platform where workers completed small tasks for pennies.

Her team designed a verification system. For each image, multiple workers would answer: does this image show the claimed object? Workers saw batches of images and clicked yes or no. To ensure quality, each image was checked by multiple workers, and answers were cross-validated. Workers who consistently disagreed with the consensus got lower accuracy scores and received fewer tasks.

The operation was massive. At peak, thousands of workers from 167 countries were verifying images. The quality control was elaborate—filtering spam, detecting random clicking, identifying workers who just wanted to earn money quickly without caring about accuracy.

Deng Jia, Li’s graduate student, ran much of the day-to-day operation. “We became experts in human computation,” Deng said. “How to write instructions that workers in different countries could understand. How to design interfaces that prevented errors. How to detect and exclude bad workers while keeping good ones motivated.”

The project consumed three years. By 2009, ImageNet contained 14 million labeled images across 22,000 categories. Li’s team had created something unprecedented—a dataset multiple orders of magnitude larger than anything in computer vision.

“I remember the day we hit ten million images,” Li said. “I had this moment of doubt. What if everyone was right? What if this doesn’t help?”

She organized an annual competition. Download a subset of ImageNet. Build a system to classify images. Submit your results. The best system wins.

The first ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge ran in 2010. The top system achieved 72% accuracy. Not great, but the organizers were hopeful. Maybe with bigger datasets, better systems would emerge.

They had no idea how right they were.

2012: The Year Everything Changed

Alex Krizhevsky was a graduate student at University of Toronto, working with Ilya Sutskever and advised by Geoffrey Hinton. Hinton had been working on neural networks since the 1980s—through the AI winter, through decades of skepticism, through the years when “neural networks” was almost a career-killing phrase.

By 2012, Hinton was in his sixties. He’d spent most of his career in the wilderness, convinced that neural networks would eventually work but watching the field move toward other approaches. He had chronic back problems and often worked lying down. He’d trained a generation of students who believed in neural networks when almost no one else did.

Krizhevsky and Sutskever decided to enter the 2012 ImageNet competition with a deep convolutional neural network. The architecture was inspired by LeCun’s work from the 1990s, but scaled up dramatically. Where LeCun had used small networks on small datasets, they would use a much deeper network on ImageNet.

The challenge was computational. Deep networks required enormous computation to train. CPUs couldn’t handle it—training would take months. But Krizhevsky was an expert in GPU programming. He wrote custom CUDA code to train the network on two NVIDIA GTX 580 GPUs simultaneously.

Training took a week. The network—later called AlexNet—had 60 million parameters trained on 1.2 million ImageNet images. Nothing remotely comparable existed in computer vision.

When the results came back, Krizhevsky thought there might be a bug. The accuracy was 85%—crushing the previous year’s winner at 74%. The gap was so large that at first, the organizers questioned whether the submission was valid.

It was. And it represented a complete paradigm shift.

Li was at the ImageNet competition when the results were announced. “I remember the room going silent,” she said. “Everyone was looking at the numbers, trying to understand what had just happened. Deep learning hadn’t been competitive before. And suddenly it was dominant.”

The error distribution told the story. Previous systems made bizarre mistakes—calling dogs “cars” or trees “chairs.” AlexNet’s errors were human-like—confusing similar dog breeds, mixing up types of birds, mistakes that suggested genuine understanding of visual categories.

More importantly, AlexNet generalized. It worked on images it had never seen, in contexts absent from training data. It had learned concepts, not just memorized examples.

Hinton later reflected: “For twenty-five years, people told me neural networks were the wrong approach. That they were a dead end. That symbolic AI or support vector machines or whatever was the future. Then ImageNet happened, and overnight everyone was using neural networks.”

The 2013 competition was dominated by deep learning. Every competitive entry used neural networks. By 2015, systems surpassed human-level accuracy on ImageNet classification. The paradigm had flipped—not because someone invented a better algorithm, but because ImageNet made it possible to train existing algorithms at the scale needed for them to work.

What Data Actually Does

The ImageNet breakthrough crystallized something researchers had suspected but not proven: learning systems scale remarkably well with data.

Data forces generalization. With small datasets, networks can memorize. With large datasets, memorization becomes impossible—there’s too much information. Networks are forced to extract patterns. A system seeing thousands of dogs in different poses, lighting, contexts can’t memorize “dogs look like this.” It must learn what makes something a dog across all that variation.

Yoshua Bengio, who had worked on neural networks through the decades when they were unfashionable, put it simply: “Small data makes systems memorize. Big data makes them understand.”

Data reveals structure that algorithms can’t anticipate. Engineers designing computer vision systems in the 1990s would hand-craft features—edge detectors, corner detectors, texture analyzers. These worked, but only for narrow cases. The features human engineers could imagine didn’t capture the full richness of visual structure.

Neural networks trained on large datasets learned their own features. Early layers learned edge detectors and color blobs—similar to what humans engineered. But middle and late layers learned features humans had never thought to design. Combinations of textures and shapes that captured subtle statistical regularities in images.

The structure was always there in the visual world. But you needed massive data to reveal it, and you needed learning systems to extract it.

Data enables depth. Deep networks have millions or billions of parameters. With small datasets, training so many parameters leads to overfitting—the network just memorizes the training set. With large datasets, there’s enough information to learn meaningful values for all those parameters.

This was key to AlexNet’s success. The network’s depth—eight layers, revolutionary at the time—was only possible because ImageNet provided enough data to train it effectively.

Data changes the economics of AI. Before ImageNet, computer vision research was dominated by algorithmic innovation. Labs competed on who could design the cleverest features, the most sophisticated architectures, the best training procedures.

After ImageNet, data became as important as algorithms—often more important. The question shifted from “what’s the best algorithm?” to “who has access to the most data?”

This had profound implications. Large companies with access to vast datasets gained advantages. Google could train on billions of images from its search index. Facebook had billions of photos uploaded by users. Academic researchers with limited data struggled to compete.

“We used to worry about who was smarter,” one computer vision researcher told me. “Now we worry about who has more data. It’s a different kind of competition.”

The Internet as Training Ground

If data was the key, the internet was the treasure trove.

By 2010, the internet contained billions of images, millions of hours of video, trillions of words of text. Every day, people uploaded 300 million photos to Facebook, posted 500 million tweets, watched 4 billion hours of YouTube. The internet was an ever-growing corpus of human knowledge, creativity, and communication.

And much of it was accessible. Websites could be crawled, images downloaded, text scraped.

For computer vision: Flickr contained hundreds of millions of photos, many tagged with descriptions. Google Images indexed billions. Instagram would eventually accumulate over 50 billion photos.

For natural language processing: Common Crawl archived billions of web pages, creating a snapshot of the internet’s text. Wikipedia provided 6 million articles in English alone, billions of words in hundreds of languages. Reddit, Twitter, news sites—massive text corpora covering every topic humans discuss.

For everything else: Amazon reviews for sentiment analysis. GitHub code for training programming models. Scientific papers for technical knowledge. Music databases for audio learning. Medical records (carefully anonymized) for healthcare AI.

The internet had accidentally become the world’s largest training dataset.

OpenAI researcher Ilya Sutskever observed in 2019: “The internet is humanity’s external memory. And we’ve discovered we can teach machines to read it.”

This created new challenges. Internet data is messy, biased, sometimes toxic. It contains misinformation, reflects historical prejudices, includes copyrighted material. Training on web scrapes meant absorbing all of this—not just facts but biases, not just knowledge but mistakes.

The datasets got names: Common Crawl, LAION-5B, The Pile. Each contained billions of words or images, downloaded automatically from the internet, filtered to remove some obvious problems but otherwise raw and unprocessed.

These datasets made possible the scaling of AI. GPT-2 trained on 40GB of internet text. GPT-3 trained on 570GB. Stable Diffusion trained on LAION-5B, containing 5 billion image-text pairs.

The internet had become the curriculum for machine learning. What machines learned reflected what humans put online—for better and worse.

The Scaling Hypothesis

As datasets grew, a pattern emerged: performance kept improving with scale, predictably and reliably.

This became known as the scaling hypothesis: for many tasks, larger models trained on more data achieve better performance, following smooth power laws with no obvious ceiling.

The evidence accumulated quickly:

In computer vision, networks with 1 million parameters underperformed networks with 10 million parameters, which underperformed networks with 100 million parameters. Each 10x increase in parameters corresponded to measurable improvement in accuracy.

In language modeling, the same pattern held. Bigger models trained on more text predicted next words more accurately. The relationship was so predictable that researchers could forecast performance of untrained models just by looking at planned size and data.

In 2020, researchers at OpenAI formalized this in “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models.” They showed that test loss improved as a power law in model size, dataset size, and compute budget. Double your parameters, reduce your error by a predictable amount. Double your training data, reduce your error by a predictable amount.

This changed how AI research worked. Before scaling laws, improving systems meant coming up with better algorithms. After scaling laws, improving systems often meant just making them bigger.

“We used to spend months trying slightly different architectures,” said one researcher at a major AI lab. “Now we just scale up and watch performance improve. It’s less intellectually satisfying but more reliably effective.”

But it also suggested a path forward. If scaling kept working—if bigger models on more data kept getting better—then maybe many of AI’s remaining challenges could be solved through scale. Maybe we didn’t need algorithmic breakthroughs. Maybe we just needed more data and bigger computers.

Whether this would continue was unclear. At some point, you run out of data—there’s only so much text on the internet, only so many photos. At some point, compute costs become prohibitive. At some point, maybe, the scaling laws break down.

But as of 2023, they hadn’t. Performance kept improving with scale. The question was how long it would last.

What the World Teaches

When you train systems on massive datasets scraped from the internet, they learn everything—the good and the bad.

They learn language patterns from billions of sentences, including grammatical quirks, common phrasings, ways humans naturally express ideas. They learn visual patterns from billions of images, including compositional rules, lighting effects, how objects relate spatially.

But they also learn biases. Stereotypes about gender and race that appear in training data get encoded in model weights. If the internet reflects societal prejudices—and it does—then models trained on the internet absorb those prejudices.

They learn misinformation. False claims repeated often enough in training data get treated as facts. Conspiracy theories, debunked science, historical inaccuracies—if it appears in the data, the model learns it.

They learn copyrighted material. When training data includes books, articles, images under copyright, models can reproduce elements of that content. This creates legal and ethical questions still being litigated.

The fundamental tension: You want systems to learn from the world as it is. But the world as it is contains things you don’t want systems to learn. You can’t cherry-pick only “good” data at the scale needed for modern AI—that would require human review of billions of examples, which is infeasible.

So researchers filter what they can—removing pornography, extreme violence, obvious spam. They try to debias training data by balancing representation. They design systems to refuse reproducing copyrighted material.

But ultimately, systems trained on massive internet scrapes learn from humanity’s digital footprint—the whole messy, complicated, biased, brilliant, flawed thing. The world teaches what the world contains.

The Data Gold Rush

By 2015, data had become the most valuable resource in AI. Companies that had been accumulating user data for years suddenly held strategic assets.

Google had:

Billions of search queries showing what people want to know

Millions of hours of YouTube videos

Trillions of words crawled from the web

Billions of images indexed by search

Facebook had:

Billions of photos uploaded by users

Trillions of social connections showing how people relate

Billions of posts revealing interests and beliefs

Amazon had:

Millions of product reviews showing purchasing patterns

Decades of sales data predicting consumer behavior

This data asymmetry created competitive moats. Startups couldn’t replicate what these companies had accumulated over years. Academic researchers couldn’t access proprietary datasets. The data-rich got richer.

Some companies saw this coming. In 2006, before ImageNet, before AlexNet, before anyone knew how important data would become, Geoff Hinton visited Google to discuss neural networks. Larry Page, Google’s co-founder, immediately understood the implications.

“We’ve been collecting data for years,” Page reportedly said. “If neural networks can learn from it, we’ll have something no one else can replicate.”

Google hired Hinton in 2013. Facebook hired Yann LeCun in 2013. OpenAI was founded in 2015. The AI arms race wasn’t about algorithms—everyone published their techniques. It was about data and compute.

This raised difficult questions. If data determines AI capability, and data is concentrated in a few companies, what happens to research openness? To academic competition? To the goal of beneficial AI for everyone?

Some researchers responded by creating open datasets. ImageNet remained freely available. Common Crawl provided internet snapshots anyone could use. Hugging Face built a platform for sharing datasets and models.

But the most valuable data—proprietary user data collected by platforms—remained locked away. The data gold rush was on, and only some players had access to the mines.

Fei-Fei Li’s gamble had paid off. ImageNet proved that data wasn’t just helpful—it was fundamental. The visual world contained patterns that learning systems could extract, given enough examples.

But her original insight went deeper. The world had always contained these patterns. They existed in the structure of images, the regularities of language, the relationships between concepts. We just needed machines that could learn to see them.

Data wasn’t artificial intelligence. But data made artificial intelligence possible. It was the substrate on which learning happened, the curriculum from which understanding emerged.

The world became the teacher. And the machines, finally, learned to learn.

Notes & Further Reading

ImageNet:

Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.-J., Li, K., & Fei-Fei, L. (2009). “ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database.” CVPR. The paper introducing ImageNet. Reading it reveals the scale of ambition—tens of thousands of categories, millions of images, all freely available. The dataset changed computer vision.

AlexNet:

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. E. (2012). “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks.” NIPS. The paper that proved deep learning works at scale. Technical but readable. The architecture details matter less than the demonstration that neural networks plus large datasets equals breakthrough performance.

Scaling Laws:

Kaplan, J., et al. (2020). “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models.” OpenAI’s analysis showing predictable power-law relationships between model size, data size, compute, and performance. Controversial but empirically supported. Changed how AI labs think about research strategy.

Data’s Role:

Halevy, A., Norvig, P., & Pereira, F. (2009). “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Data.” IEEE Intelligent Systems. Google researchers arguing that simple algorithms with large datasets outperform sophisticated algorithms with small datasets. Written before the deep learning revolution but prescient about data’s importance.

Crowdsourcing:

Deng, J., et al. (2010). “What Does Classifying More Than 10,000 Image Categories Tell Us?” ECCV. Details about how ImageNet was constructed using Mechanical Turk. Shows the engineering challenges of crowdsourcing at massive scale—quality control, worker motivation, spam detection.

The Human Side:

Fei-Fei Li’s TED talk “How We’re Teaching Computers to Understand Pictures” (2015) tells the ImageNet story accessibly. Her book The Worlds I See (2023) provides personal narrative about building ImageNet while navigating academia as a young professor.

Data Biases:

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). “Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification.” Shows how biases in training data lead to biased systems. Face recognition worked better on light-skinned males than dark-skinned females—reflecting demographics of training datasets.

Common Crawl:

The nonprofit organization provides free snapshots of the web for research. Billions of pages, petabytes of data, updated monthly. Powers much of modern NLP research. See commoncrawl.org.

On Scale’s Limits:

Bender, E. M., et al. (2021). “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” Questions whether scaling alone solves AI’s challenges. Raises concerns about environmental cost, bias amplification, and whether understanding emerges from scale. Important counterpoint to scaling optimism.