Roads to a Universal World Model

How AI Learns to Understand the Physical World

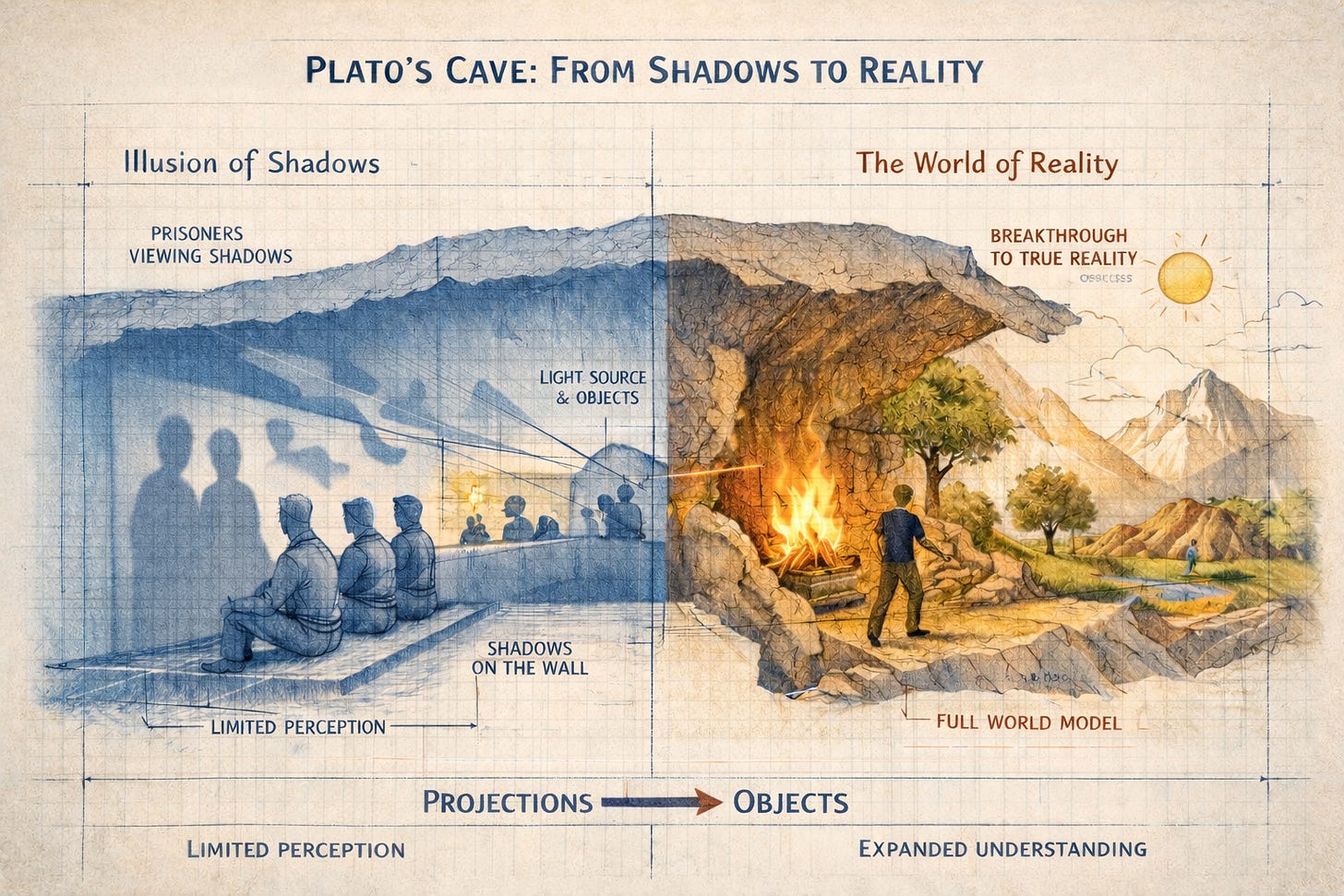

“To them, the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.” — Plato, Republic

A fourteen-month-old reaches for a cup on a kitchen table. She wraps her fingers around it, pulls it toward the edge, and pauses. Then she pushes it off. The cup falls. It hits the floor. Milk explodes in every direction.

She is not surprised.

She did not need to see the cup fall to know it would fall. She did not need to feel the impact to know there would be one. Somewhere in her developing brain, a model of the world predicted the outcome before it happened. Gravity pulls things down. Unsupported objects drop. Liquids splash. She tested her model against reality, and reality confirmed it.

This is a world model: an internal representation of how things work that lets you predict what will happen next. A dog chasing a ball anticipates where it will bounce. A crow dropping a nut onto a road predicts that a passing car will crack it open. A human catching a ball thrown at an unexpected angle computes, in milliseconds, the trajectory, adjusts the hand, and intercepts. No equations. No conscious reasoning. Just a model running silently in the background, simulating physics faster than physics itself unfolds.

Now consider the most advanced AI systems in the world. They can write poetry, pass the bar exam, and generate photorealistic video of things that never happened. But ask a robot to pour coffee into a mug it has never seen before, on a table it has never encountered, and it will likely fail. Not because it lacks skill. Because it lacks understanding. It has no model of the world.

This is the gap. And closing it is arguably the most consequential open problem in artificial intelligence right now.

Shadows on the Wall

The question of how to build an accurate picture of reality from incomplete information is not new. It is, in fact, one of the oldest questions in philosophy.

Around 380 BC, Plato described prisoners chained inside a cave, facing a blank wall. The chains fixed their heads in place so they could not turn around. Behind them, a fire cast shadows of objects passing between the flame and their backs. The prisoners had never seen the objects themselves. They knew only the shadows: flat, flickering, incomplete projections of a three-dimensional reality they could not access.

For Plato, this was a metaphor for the human condition. We perceive shadows, not reality. Understanding comes from escaping the cave.

Twenty-four centuries later, this metaphor maps with eerie precision onto the central problem of AI world models. A robot perceives the world through sensors: cameras capture pixels, force sensors measure pressure, encoders track joint angles. These are shadows on the wall. They are projections of a richer, deeper reality: the causal structure of the physical world, with its gravity, friction, momentum, elasticity, and ten thousand other regularities that govern what happens when you push a cup off a table.

A world model, as AI researchers currently conceive it, is an attempt to infer the world outside the cave from the shadows. Not to escape the cave. Not yet. But to build a model good enough to predict what the shadows will do next, and eventually, to act on that understanding.

There is no single strategy for building such a model. There are many. Each with different strengths, different blind spots, and different bets about what matters most. This series traces those strategies.

A Very Old Idea, a Very New Moment

The concept of machines building internal models of reality has its own history, and it starts not in Silicon Valley but in wartime Cambridge.

In 1943, a Scottish psychologist named Kenneth Craik published a slim book called The Nature of Explanation. In it, he proposed something radical for his time: that the brain works by constructing “small-scale models” of the external world, then running those models forward to predict what will happen next. “If the organism carries a ‘small-scale model’ of external reality and of its own possible actions within its head,” Craik wrote, “it is able to try out various alternatives, conclude which is the best of them, react to future situations before they arise.”

This was not a metaphor. Craik meant it mechanistically. The brain, he argued, is a prediction machine, and its predictions are generated by internal models that mirror the structure of reality. You do not need to build a physical bridge and wait for it to collapse to know whether the design is sound. You build a model, in your head or on paper, and test it there.

Craik died in 1945, struck by a car while cycling in Cambridge. He was thirty-one. His idea survived him. It passed through cybernetics and cognitive science, through control theory and robotics, gathering different names and different formalisms along the way. In 1991, Richard Sutton built Dyna, an AI architecture where an agent learned a model of its environment and used it to “dream” about possible futures. In 2018, David Ha and Jürgen Schmidhuber published a paper titled, simply, “World Models,” in which an agent learned to race cars by first learning a compressed representation of the game world, then training entirely inside its own imagination.

But for decades, the idea remained more promise than practice. Learned world models were fragile. Small errors compounded. The imagined world diverged from the real one after a few steps, making the model useless for anything beyond the near future. The concept was elegant. The execution was brutal.

What changed? Three things converged in the 2020s.

First, scale. The transformer revolution that powered large language models also provided architectures capable of learning rich, high-dimensional representations of visual and physical data. The same attention mechanisms that let GPT predict the next word could, in principle, learn to predict the next frame of video, the next state of a physics simulation, or the next consequence of a robot’s action.

Second, data. The explosion of video on the internet created an enormous corpus of implicit physics lessons. Every video of a ball bouncing, a door closing, a liquid pouring, or a car turning contains information about how the world works. No one labeled this data. No one annotated the physics. But it was there, waiting for models powerful enough to extract it.

Third, necessity. Language models hit a ceiling. They could process and generate text with remarkable fluency, but they had learned language, not physics. The same was true of their multimodal descendants. Even the most advanced vision-language models were fundamentally language-first systems: vision entered at the encoder, then got routed into a language backbone. Most of their parameters were allocated to knowledge, recognizing that a pattern of pixels is a coffee mug. Very few encoded what would happen if you knocked it off the table. For AI to move beyond language, into robotics, autonomous driving, manufacturing, and scientific discovery, it would need to understand physics. It would need a world model.

Next-word prediction built the first generation of foundation models. Next-world-state prediction may build the second.

The Cake and the Cherry

No one has articulated the stakes of this problem more provocatively than Yann LeCun.

In 2016, LeCun, then heading AI research at Facebook, offered his famous cake analogy at the NIPS conference. "If intelligence is a cake," he said, "the bulk of the cake is unsupervised learning, the icing on the cake is supervised learning, and the cherry on the cake is reinforcement learning." He later replaced "unsupervised" with "self-supervised," but the analogy stuck. The analogy evolved over the years. And its sharpest version targeted something deeper: not the learning paradigm, but the medium. Language models, despite being self-supervised themselves, were learning from text, a thin, lossy compression of human knowledge. The real substance of intelligence, LeCun argued, lies in learning to predict and model the physical world.

By late 2025, he had left Meta to launch AMI Labs, a Paris-based startup valued at $3.5 billion before writing a line of product code. Its mission: build world models using JEPA, his Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture. Around the same time, Fei-Fei Li’s World Labs shipped Marble, a system that generates explorable 3D worlds from text and images. NVIDIA continued building out Cosmos, its platform for physical AI simulation. Google DeepMind released Genie 3. Runway launched its own world model. The word “world model” appeared in investor pitch decks with the same frequency that “large language model” had two years earlier.

Something had shifted. The idea that had simmered for eighty years, from Craik’s slim wartime book to Ha and Schmidhuber’s racing car dreams, was suddenly at the center of the industry’s attention.

But attention is not understanding. And this is where most coverage of world models fails. It treats them as a single concept, a monolithic next step after LLMs. In reality, the landscape is fractured. Multiple communities, working from different traditions, with different assumptions and different architectures, are all converging on the same goal from very different directions.

Understanding those directions, where they came from, where they agree, and where they fundamentally disagree, is the key to understanding what comes next.

Five Roads, One Destination

This series traces five distinct paths toward a universal world model. Each grew from a different tradition. Each makes a different bet about what matters most. And each reveals something the others miss.

The Dreamer's Road begins in reinforcement learning, with the idea that an agent can learn faster by imagining possible futures. From Sutton's Dyna to Hafner's Dreamer 4, this road asks: what if you could practice inside your own imagination? Its arc bends from agents that dream about grid worlds to agents that learn physics from watching video, then train entirely inside their own dreams. The key insight it offers is that a world model does not need to be photorealistic. It needs to capture the structure that matters for action.

The Physicist’s Road starts from first principles. If you know the equations governing a system, you can simulate it precisely. From flight simulators to NVIDIA’s Omniverse, this road builds the world from physics up. Its key insight: simulation gives you infinite data and perfect control, but it breaks at the boundary of the known. You can simulate a world you understand. You cannot simulate one you don’t.

The Cinematographer’s Road emerges from video generation. When models trained to predict the next frame of video unexpectedly began obeying physics, shadows falling correctly, liquids pouring realistically, objects persisting behind occluders, researchers realized that video prediction might be a backdoor to world understanding. The key question this road raises: is this real understanding, or sophisticated pattern matching?

The Robot’s Road is the hardest. Robotics imposes constraints that no other domain does: real physics, real-time feedback, real consequences for errors. A video model can fake gravity. A robot cannot. This road’s key insight: a world model without action is incomplete. Predicting what will happen is fundamentally different from predicting what will happen if I do something.

The Architecture Debate is not a road at all, but a crossroads. It asks the deepest question: what should a world model even look like? Should it predict pixels, frame by painstaking frame? Or should it predict in a more abstract space, capturing the structure of what happens without reconstructing every visual detail? This is where Plato’s Cave resurfaces as a live technical argument: predicting shadows, or predicting the objects that cast them? The future is most uncertain here. It is also most exciting.

After tracing each road, the final two parts examine the convergence. Why are these separate traditions starting to use the same ingredients? What would a true universal world model actually look like? And how far are we from building one?

What This Series Is and Isn’t

This is not a survey paper. It is not a catalog of every world model published in the last five years, organized by architecture and benchmark score.

It is a narrative. It traces the ideas, the people, and the decisions that brought us to this moment. It argues that the convergence happening now is real and significant, but that the path forward is far less clear than the hype suggests. It aims to give readers, whether they are engineers, investors, researchers, or simply curious, the conceptual framework to evaluate what they read next about world models. Not just “what is this?” but “why does it matter, and what are the bets it’s making?”

The toddler who pushed the cup off the table did not need a PhD in physics. She did not need ten billion training examples. She built a model of the world through a few months of reaching, grasping, dropping, and watching. That model is imperfect, incomplete, and constantly being updated. But it works.

Building something like that in a machine is the goal. We are closer than we have ever been. We are also further than most headlines suggest. Understanding why both of those statements are true is what this series is about.

Next: Part 1, "The Dreamer's Road," traces the reinforcement learning path to world models, from Rich Sutton's 1991 insight that agents could learn by imagining, through decades of elegant failure, to agents that master Minecraft by watching videos they never acted in.